Alla Efimova

Introduction

My friend Moira Roth died a year ago, on June 14, 2021. Four years before, she invited me to her favorite Berkeley cafe, Nabolom, where she read and wrote in the mornings. I often joined her at the window table to share a coffee and a pastry but this was not an ordinary meeting.

I had first met Moira at this same cafe a decade and a half earlier, having only known her by reputation as a feminist art historian, a specialist in performance art, and a beloved professor at Mills College in Oakland. Suddenly and easily we became collaborators. More than anything else, I was fascinated with Moira’s alter ego, a fictional character named Rachel Marker, the protagonist of a book she began in 2001. Since our first meeting, I became a reader, a curator, and a participant in the unfolding of her project, Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker.

Moira Roth at Nabolom, 2013. Photo: Alla Efimova

After having taught art history for decades and publishing numerous scholarly books and articles, Moira began working on this epistolary, image-laden book in her mid-60s. It evolved in a non-linear fashion, with many installments and numerous revisions. A Czech Jew, a poet, novelist, and a playwright, the novel’s protagonist, Rachel Marker, bore witness to 20th-century history, recording, reflecting, and selectively forgetting it. Moira wrote chapters of the novel during her prolonged stays in Europe: Berlin, Prague, Paris, and Madrid. Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker was Moira’s way of being in touch with history — the history that shaped her as a British-born, European-educated scholar, the history that she taught to the young women at Mills, and the history that stubbornly protruded into the present.

The novel was also marked by grief for Moira’s mother. Two mothers, actually: her biological mother who passed away, and an “adopted” Jewish mother, Rose Hacker, who died in 2008. Writing in the voice of Rachel Marker — a fictional avatar but a thinly disguised version of Moira’s mother figures — allowed her to break free from the constraints of academia, let go of footnotes and citations, and also to reinvent herself as a poet, novelist, and a playwright. In fact, simultaneously with working on the novel, Moira was writing other fiction and poetry, such as The Library of Maps, which is closely connected to and often intertwined with Through the Eyes Rachel Marker.

Parts of Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker were published in periodicals, others were performed as dramatic readings. However, Moira resisted a conclusion and kept adding new chapters to the manuscript. In an attempt to encourage her to finish and publish the novel, I organized an exhibition at the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at the University of California Berkeley, which I had directed from 2010 to 2015. In Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker: A Literary Installation by Moira Roth we displayed the manuscripts, the artifacts that belonged to the real characters that Rachel Marker was based on, as well as video and sound projections to bring the characters and history to life.

Instead of using the occasion of the exhibition to complete the novel, Moira used it as a springboard to develop still more characters and plots. I came to believe that there was a deep-seated reason for her to keep the project going, to keep Rachel Marker alive and close by.

Moira surprised me at our meeting at Nabolom on June 23, 2017. Handing me a bound copy of the manuscript, she indicated that she had finished the novel, and asked me to edit and publish it. I was astonished but could not refuse a request that felt like a generous gift. I did not yet know that only a few months later a group of us would be moving Moira to an assisted living facility and, soon thereafter, to a memory care unit where she lived with dementia.

While organizing Moira’s professional archive over the past year, I learned a lot more about Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker and will get it edited and published as promised. I also know why I see Moira’s project as a gift; I identify with who Moira was when she turned to fiction. I myself have now turned sixty, become a widow, and faced my own mother’s aging and decline. I understand Moira’s desire to commune with the dead through writing and, to that effect, the need to recalibrate one’s voice, discarding the clinical writing conventions of our profession. I am approaching my task with deep empathy, not just as an art historian but as a fellow genre-defying author. The text that follows is my experiment with writing a tribute — a tribute to Moira Roth and Rachel Marker.

The Ocean

August 31, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

Last Friday we walked to the edge of the world, to face the heaving Pacific. I took off my shoes to feel the sand, the tiny pebbles ground to dust by the ocean through eternity. We carried your ashes in a black box. When we opened the box, there inside was a plastic bag holding the dust of you. “Is that Moira?” asked Suzanne.

August 27, 2021, Rodeo Beach, California. Photo: Alla Efimova

We brought roses and rose petals. There were roses from your garden, and roses from your friends’ gardens, and some must have traveled across the ocean from the countries where entire fields of roses bloom all year. We stood in a circle and formed a ring with the roses and talked about our love for you and what we learned from you. Edit everything twelve times. Always reward yourself. Do not start an email with an “I.” Make-believe is more interesting. A flock of pelicans flew above us, gliding gracefully, keeping close to one another, also in a quiet formation.

We each took a part of you — a handful — and walking into the breathing ocean, spread the ashes and tossed the roses into the waves. With each inhale, the ocean took you in; with each exhale, it returned the roses to the shore. The pink, orange, yellow, cream and red petals dotted the sand, mixing with the sea foam, resting and waiting.

Rose was the name of the mother you adopted, the woman you chose to be your family: Rose Hacker, the inspiration for your fictional character Rachel Marker.

You really knew how the living can talk to the dead. Rachel Marker wrote letters to the dead Franz Kafka. I am going to write to you, Moira, and let you know how I am getting on with the work you gifted me, the news of Rachel Marker, and my thoughts on what I am seeing.

You wanted to see history through the eyes of Rachel Marker, to inhabit the past. You embodied the character of a threatened, fleeing Jew in order to expose yourself to danger. You wanted to feel what Rose felt. Now you are connected with her through the ocean’s breath, through the flapping of pelicans’ wings, through the sand and the dust we walk on, through the petals dissolving in salt water and through the words you handed off to me.

The Bakery

September 5, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

Do you remember the first time we met? I walked with a friend down Russell Street to the corner of College Avenue to get coffee. This section of the street is a secluded lane between two busily trafficked avenues. The old elm trees, where rare ospreys nest, form a dense shade canopy. Lush gardens surrounding homes of a vintage unusual for California make for a serene walk.

There, at an outdoor table in front of Nabolom, my friend recognized you. We were introduced. I only knew you by reputation then and here you were, so interested and interesting, with your keen eyes and your soft voice. Right away, I met the two of you: Moira Roth and Rachel Marker, you and your shadow.

I was running The Magnes, the Jewish museum at the other end of Russell Street. Housed in a late-nineteenth century mansion built by a railroad magnate, the museum was tucked away behind a long brick wall, up above a terraced garden, obscured by old-growth trees. Since the 1960s, it had ingested tens of thousands of Jewish objects, books, and documents from all over the world, the artifacts orphaned by exterminations and expulsions, the evidence of lives and deaths. The building was overfilled, creaking at the sides, bursting at the seems. I was working to save the museum and the memories it sheltered.

Right away I recognized Rachel Marker, a fictional Czech Jew traversing the twentieth century, witnessing its monstrosity, looking for a refuge, writing to remember, keeping a record. I asked you to bring Rachel to the museum and to read from the book you have been absorbed in for two years while inhabiting Rachel’s character, both being her and observing her. Isn’t this how it began?

From then on, we would meet regularly at Nabolom to scheme and to plot. The cafe, also dating to the sixties, was hanging on by a thread, fighting to keep alive such unpopular ideas as “the collective.” While the ideas were fading, the breads and danishes on the baker’s racks were alive with ferment and smelling deliciously sour.

The short tree-covered stretch of Russell Street connected the two sites where Rachel came to live, between us. At Nabolom, you kept breathing life into Rachel while inhaling the aroma of the bakery’s yeast and sugar in the mornings. At the museum, I had tried to breath life into the bloated accumulation of things, injecting a living culture into the tumorous memorial. We both needed Rachel Marker to come face to face with the past.

The Binding

September 15, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

The first time you handed me a printout of the book you were only a couple of years into writing it. The gesture took me by surprise. Rachel Marker’s letters to the dead Franz Kafka, set in Times Roman 12, were carefully formatted and interspersed with images. The date stamp on the pages suggested that the typescript was a draft, still in the editing stages. Yet the pages were spiral bound in the print shop, and you wrote by hand “To dear Alla E.” on top of the cover page as if inscribing a freshly published tome. Why was I surprised? I think you challenged my ideas about the protocols of sharing what we write. I was not yet a friend but you trusted me to see the work-in-progress, you drew me into your circle, and I willingly became an accomplice in your exploits. The bound and signed pages you handed to me signaled an impending conclusion which you would continue to resist for many more years.

The copies of the consecutive, ever-expanding typescripts started accumulating on my shelves, in my desk bins, in the drawers. You wrote another chapter and edited two earlier ones. You changed the images and renumbered parts. You re-ordered sections and started new chapters. There were multiple versions, some with red cover pages and some with black vinyl backings. Pages were held together with coil bindings, plastic comb bindings, or tape bindings. At times the book had twenty four parts, and other times only thirteen. The circle of your trusted friends who received the gifts of these bound volumes kept expanding. How many of us were such recipients, your readers and confidants?

Moira Roth, Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker, typescript, 2010. Photo: Alla Efimova

A manuscript is bound when it’s completed. Off to the publisher it goes, neatly packaged and addressed. A finished novel is inscribed to a reader. A play is staged. A musical composition is performed. Every year you had a new set of copies made at the local print shop yet avoided a conclusion. Did you and Rachel now meander together through the landscape of memory, traveling through these pages, holding on to each other? You could not let go of Rachel, could you? You were bound to each other.

The Menu

June 28, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

A few weeks after you left us, I invited Sue over for dinner. You are fortunate to have had a friend as devoted and capable as she is. Of course, I designed and printed a menu, as you always did for the gatherings at your house. A simple dinner menu would describe the dishes with a grand flourish. You taught me this game of turning the simplest of meals into a royal repast, and I enjoy doing it, always thinking of you and your fancies.

Moira Roth, A Dinner for Sue, 2014. Courtesy Sue Heinemann.

Like a girl inviting adults to a pretend tea party, with miniature porcelain cups and dainty pastries, you drew us into the land of make believe, into the wonderland where everything was crisper, wittier and more enchanting. I thought you practiced what you preached: the menus transformed the dinners into performances; they were playbills signaling the anticipation of a curtain about to rise.

Your scrumptious menus are fused in my memory with Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker. They were printed in the same font, on the same paper, with images pasted in, the same way you composed the book; the same way you invented a character who you stepped into, saw and spoke through; the same way you invited your friends into the world you concocted; the same way you gifted to us not just the real sustenance of food but your language, printed and bound, arranged and incarnated.

Stepping Out

September 27, 2021, New York

Dear Moira,

The framed poster of our museum exhibition has been hanging in my office, above every desk I worked at, since 2014. The photograph of Rose and her father, taken in Berlin in the 1930s, is haunting. It looms large on the poster, but I remember it as a small sepia image — a minute fragment of history — in your hands. We blew it up life-size for the exhibition entrance. Such an unusual photograph: the two figures are walking down a city street, facing the camera; they are caught in mid-step. Who could have taken this photograph, who was behind the camera? When I look at the poster — as when I did at the exhibition — it seems that we are moving toward each other, destined to meet.

Perhaps I am so obsessed with this image because the premise of the exhibition was to bring to life the real women behind the Rachel Marker character. We told Rose’s story through her writings, photographs and objects such as that old hand mirror that you treasured. Not a fictional artifact, it belonged to the real person whom you cared deeply for. From the silent pages of your typescript, the characters stepped into the gallery, now filled with movement and sound. It’s as if introductions were made; we moved into their space, and they temporarily inhabited ours.

Remember how we struggled with what to call this exhibition and finally settled on “a literary installation by Moira Roth?” We invented a genre that implied a metamorphosis from two into three dimensions, from words on a page to objects in space. Does it not remind you of those vintage pop-up greeting cards that unfold into intricate scenes when opened?

The Play

September 30, 2021, New York

Dear Moira,

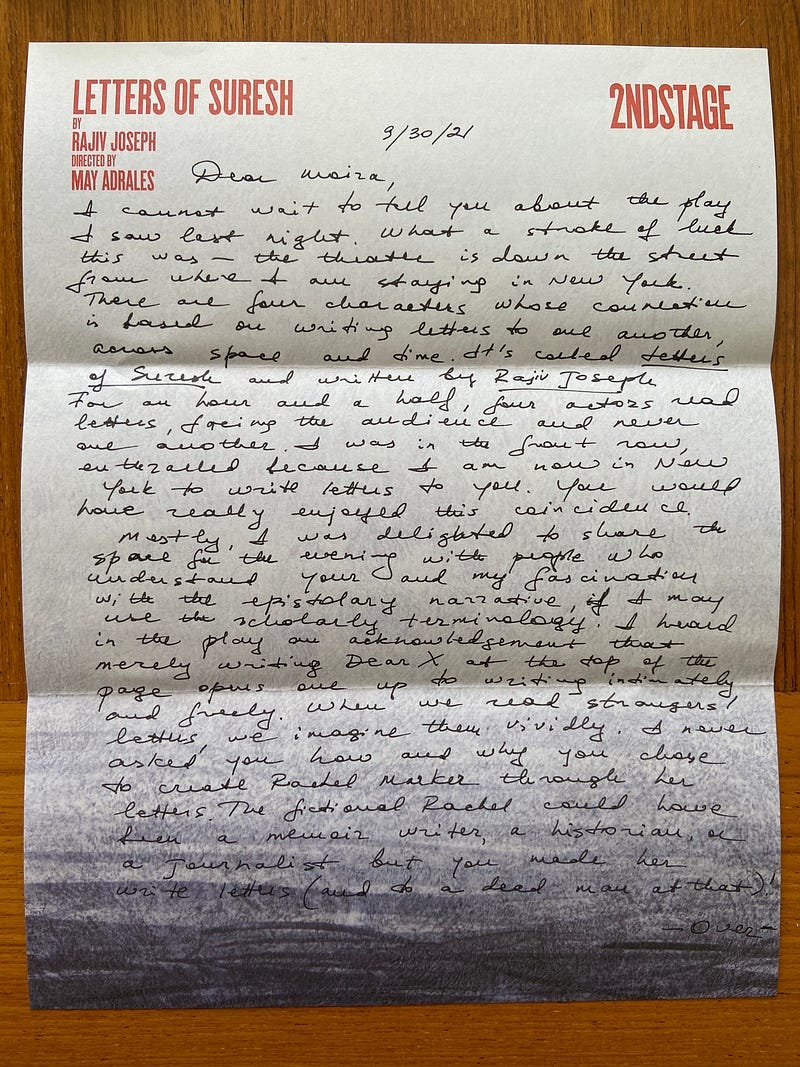

I cannot wait to tell you about the play I saw last night. What a stroke of luck this was — the theater is down the street from where I am staying. There are four characters whose connection is based on writing letters to one another, across space and time. It’s called Letters of Suresh and was written by Rajiv Joseph. For an hour and a half, four actors read letters, facing the audience and never one another. I sat in the front row, enthralled, because it was the first time in almost two years that I’d seen a live performance and also because I came to New York to write letters to you. You would have really enjoyed this coincidence.

Mostly, I was delighted to share a space for the evening with the people who understand our mutual fascination with letters. What I heard in the play was an acknowledgement that merely writing “Dear X” at the top of the page opens one up to writing intimately and truthfully. I never asked you how and why you chose to create Rachel through her letters and diaries. The fictional Rachel could have been any kind of writer, but you made her write letters (and to a dead man at that.)

At the theater last night the ushers handed out a package, containing, among other things, an envelope with two sheets of pre-printed stationary and instructions. It read: “…we hope the Letters of Suresh will kindle a desire to write letters. You may wish to send a letter to someone you care about, or to hold onto the letter as a personal keepsake. ”

Well, my desire did not need kindling. I am writing this letter on the theater stationary and mailing it to the playwright.

The Gift

August 20, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

I did not really believe you at first when you handed me the final version of the book and said: “It’s yours now.” For years I had nudged you, trying to persuade you to declare it done and get it published. But you resisted the ending, continuing to invent new characters and situations, drawing ever more people into your plot. At a certain point I just gave up. I thought that you and Rachel needed each other to keep going, and no-one could close the book on the two of you.

One morning you asked me to come to Nabolom, where I had first met you more than a decade earlier, and dropped a bombshell on that wobbly wooden table by the window. It was a gift, but a bombshell. Remember, I invited Robin a few days later to join us for coffee — I did not tell you that, of course, but I needed a witness — and you repeated it in front of her: “Rachel is now yours.”

Did I have a hunch then that your memory had started slipping and that your mind had become confused and confusing? Was I aware that you were slowly abandoning us so as to fully immerse yourself in the fictional world? Did I foresee that dementia would slowly spirit you away? I did not, but I could tell that a bomb had exploded.

Soon, we would move you to the “village.” You seemed content and at peace, having relinquished the mundane cares and obligations of this world. At first, you read and wrote, watched films, went on outings with friends. Later, your room was plastered with post-it notes, prompts, and reminders. And then you appeared fully transported to a dreamland and could not be bothered with the anchors of our reality.

I must confess that until you left us completely in June, dear Moira, I held on to the book. I could not make the definitive edits and annotations, could not write an introduction and conclusion, could not hand it off to a publisher, neatly bound and wrapped up. I could not expel Rachel from the intimacy of our triad. We all kept each other going for three years. I needed to hold on. But finally, I am ready to let go. The book is no longer mine alone.

Memory Care

September 15, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

Our last visit made me sad. You did not really know who we were — Anna and I — when we came to see you at “the village.” We brought flowers and left them in a vase in your room, hoping you would enjoy them when awake.

I talked and you nodded, letting out a smile once in a while. How painful and frustrating it was to talk at you. I used to depend on your complete attention when we were together, working or plotting or gossiping. Now, I selfishly wanted your regard, your full attention, again, but you were immersed in your world, facing inward . Where were you?

In a memory care unit. How does one care for memory? For the last twenty years years of your life you had taken care of Rachel’s memory, looking at history through her eyes, witnessing and recording. You pulled up words and images from the bottom of that well. You memorialized Rose, her best friend Alice, and even my grandmother. You arranged their imagined meetings in phantom sites in the cities that had been bombed and then rebuilt.

Sinking into a soft grey couch in “the village” hallway, I strained to tell you the news, mine, yours, and that of our friends. You were tired and wanted to rest. In your room, you curled up like a child, falling asleep easily and swiftly. I was relieved to stop talking and let you dream. After sitting by your side in silence, Anna and I tiptoed into the quiet hallway and then stepped out into the bustling street. I was sad because I missed you but at ease because you and Rachel, together in a dreamland, were taking care of memories.

The Letters

September 16, 2021, Berkeley

Dear Moira,

Today, on Yom Kippur, I thought of Yom HaShoah three years ago. On Holocaust Remembrance Day in April 2018 I came to visit you and Rachel at the “village.” It’s really a day of commemoration — the victims of the Shoah and the martyrs of the Jewish resistance. The day also commemorates the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. I know you are not big on commemorating but rather on remembering — and that’s something else.

I brought along my friend Avi to videotape you reading passages from Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker. He also took some photos that you told me you liked a lot. One of the passages I had asked you to read was a letter from Rachel to Kafka, written in Paris in 1940 two weeks after the Nazi invasion. I must have chosen it thematically — Rachel escapes Prague to Paris, where as a Jew she is alone and no longer safe. The letter is full of foreboding. I’ll copy the passage here to remind you.

July 6, 1940, Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris

Dear Franz,

Since my miraculous escape to Paris from Prague last September at the beginning of the war, I have not written to you because I did not know where to leave my letters. As you know I used to give them daily to the waiter at the Old Town café and he would store them in the trunk that once belonged to you.

Perhaps eventually Hitler will be defeated and I will be able (if I am still alive) to return to Prague? If so, will I find the waiter still in the café, I wonder?

How can I briefly summarize for you my experiences and feelings since coming to live in Paris, which was taken over by the Nazis two weeks ago?

My life has been very solitary. I live next to the Montparnasse Cemetery and often visit it to sit by Charles Baudelaire’s grave.

Today, however, I have come to the Père Lachaise cemetery to leave this letter for you, together with flowers, on Marcel Proust’s grave. Though you and he never knew one another, I imagine exchanges between you as part of Letters to the Dead, which I have just written at the request of the Mute Players that they will ceremoniously over a hundred years place in different cemeteries around the world.

I know that you and Proust will have much to say both to one another, and to the Dead.

Photo: Moira Roth

I shudder when I read and listen to this letter now, when you have become one of the Dead, whose remains are graced with flowers. What are these instructions about? Writing to the dead writers — Baudelaire, Proust, Kafka — for a hundred years? Are you saying that we must engage in the act of writing to keep memory alive? Not to commemorate or memorialize but to remember by scribbling and scrawling, pushing pencil and putting pen to paper?

When I asked you to read Rachel’s letter from Paris, I thought that we were paying tribute to the victims of the Holocaust, but now I understand: it was the day you gave me the instructions for speaking with the Dead.

Moira Roth reading from Through the Eyes of Rachel Marker, May 2018. Photo: Avi Stachenfeld.